Misc. Seedlings (Non-Fruit)

Let's get a little more diverse! We are happy to see a growing interest in folks growing seedlings! They are an excellent way to increase diversity for both nature and your palate!

Seedlings may share some characteristics with their mother plant but there will be natural variation creating a unique plant with every seed, as unique as the differences between you and me. Remember when planting seedlings it's best to plant a few (2-3) for pollination.

Sort by:

29 products

29 products

Species: Corylus americana

History: American hazelnuts are native to eastern and central Canada and the US. The nuts are an important food source to many animals and as such the shrubs are most often cultivated for planting in native and wildlife gardens. Indigenous peoples also use the shrub for medicinal purposes.

Why We Grow It: This thicket forming native shrub produces nutritious hazelnuts and fodder for animals. It is an excellent species to incorporate into a pasture/grazing system.

Species: Platanus occidentalis

History: American sycamores (aka American planetree, buttonwood, and water beech) are native to the United States, the most northern parts of Mexico, and the most southern parts of Canada. The bark has traditionally been used by indigenous peoples to make bowls for gathering berries and the wood has been used to make butcher blocks. The tree itself was common as a street tree but its susceptibility to anthracnose made it visually unappealing and it was replaced by the London planetree. The Buttonwood Agreement, the founding document of the New York Stock Exchange, is named for this tree because it was signed under an American sycamore in 1792.

Why We Grow It: American sycamores are an attractive tree with visually unique camo-like bark and curious brown little seed balls that hang on through the winter. They can get quite tall and are a good wildlife tree. Just be mindful that the roots are good at clogging drain pipes so be mindful where you plant it!

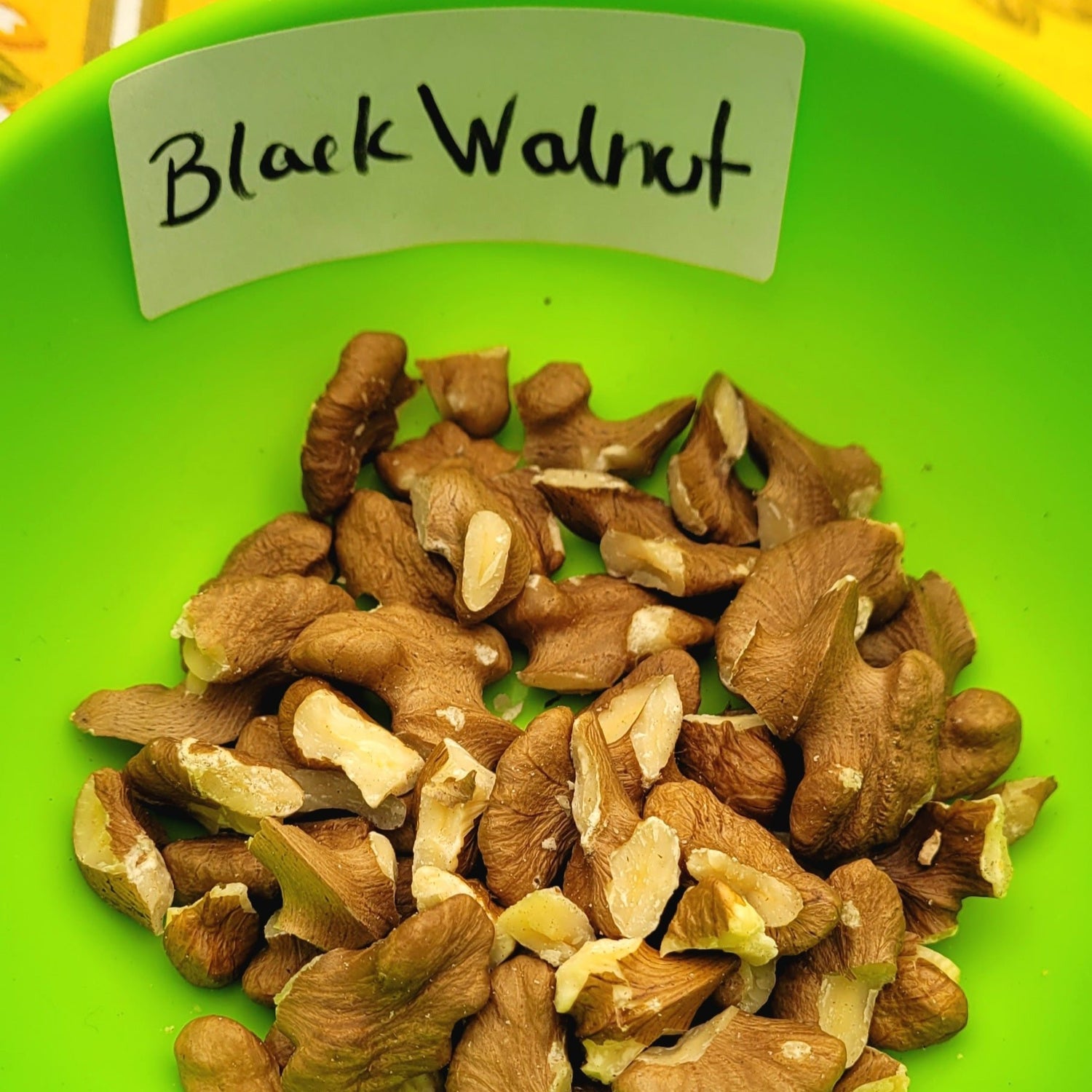

Species: Juglans nigra or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: Native to much of the eastern and central United States and southern Ontario, Black Walnut has long been used as a source of food, dye, lovely dark wood, and as an ornamental tree. Although it is said to have a better flavour than the English walnut, the Black walnut remains less popular due to the increased difficulty of harvesting the nut meat from within the husk. Black walnut is also infamous for being allelopathic, meaning it secretes toxic chemicals (juglones) into the soil to reduce plant competition.

Why We Grow It: Black walnut is a beautiful tree that produces nuts with a stronger flavour than that of English walnuts. The sap can be boiled to make walnut syrup, which tastes very similar to maple syrup but with notes of caramel and butterscotch. Also, the husks can be used in brewing beer!

Be mindful of the juglones in the in the roots/nut husks, they are toxic to many other species. They require a buffer of about 50'/30m from the edge of the trees canopy for juglone-sensitive plants. This article from The Garden Hoe has a helpful list of plants that tolerate juglones. However there are recent (2019) studies showing healthy soil high in organic matter and mycorrhizal fungi actually reduce the toxicity of juglones suggesting many plants can grow below juglans species in a healthy ecosystem - it will be interesting to see more study done in this area!

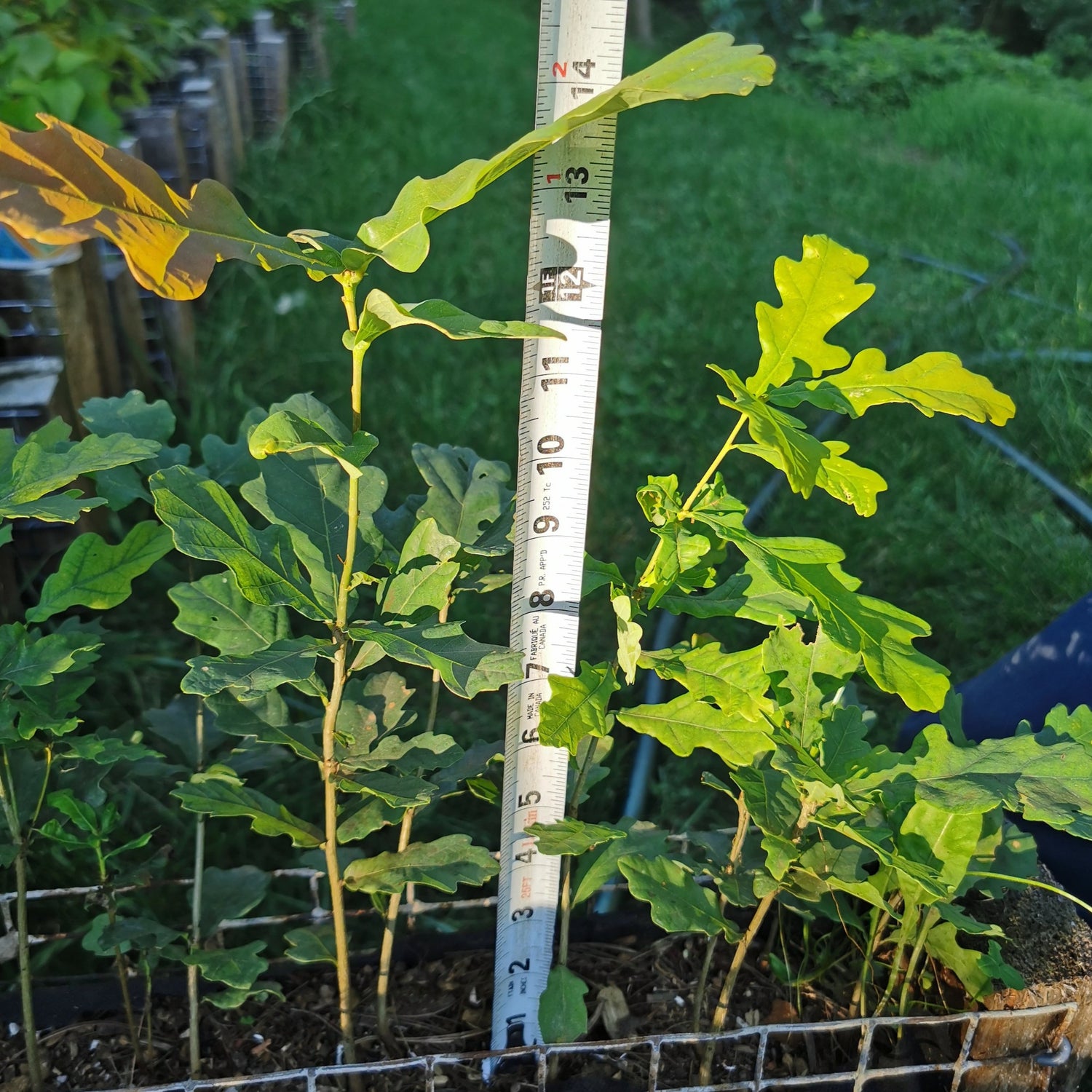

Species: Quercus macrocarpa or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: Burr Oaks are native to much of the central United States with populations in Canada stretching from Alberta to New Brunswick. The tree has been planted ornamentally across North America and the durable wood has uses such as flooring and barrels. The acorns, the largest in North America, are a source of food for many animals and indigenous peoples use the bark medicinally. Numerous towns and a book of poetry are named after this tree.

Why We Grow It: The Burr Oak's acorns have slightly less tannins than other oaks, making it the preferred choice for eating. It still requires processing to remove tannins, but once done, the nuts can be toasted, and/or made into flour and used in baking. It is one of the largest oaks in North America, making quite the specimen when full grown.

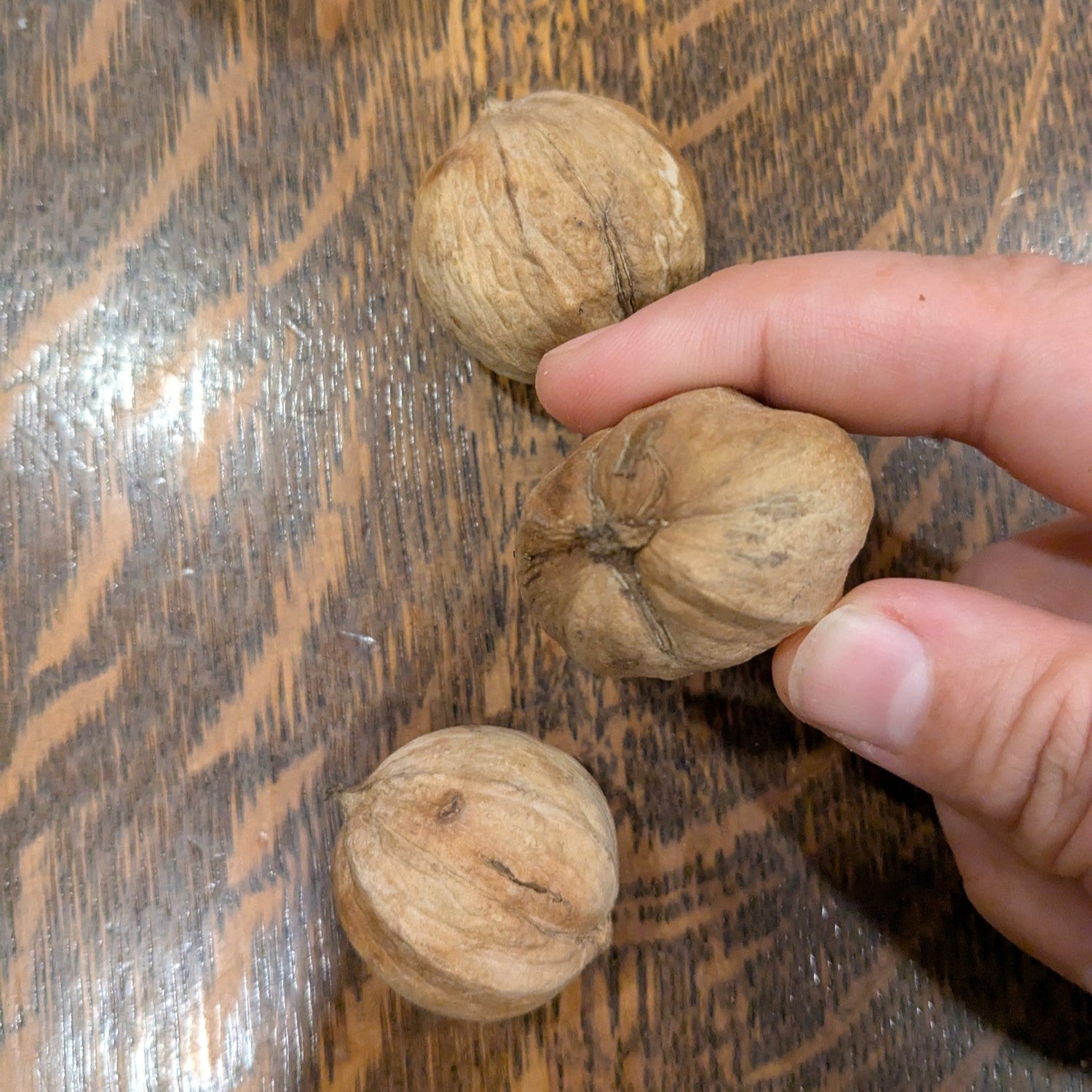

Species: Juglans cinerea or hybrid. NOTE: Butternuts are known to hybridize readily with other closely related species so there is no guarantee on whether these seedlings are pure, though the mother trees appear very true to type.

History: Butternut is an endangered tree native to southeastern Canada and the eastern United States where they grow naturally along sunny stream banks with rich, well-draining soil. The nuts have been used as a source of food and made into a butter-like oil by indigenous peoples. The trees have also been used for making syrup, furniture, and woodcarving. 'Butternut' became a derisive term for people living in the southern US since their clothes were dyed using butternuts, and the name later applied to Confederate soldiers. Unfortunately, Butternuts are highly endangered today due to Butternut Canker which has decimated their population within two decades.

Why We Grow It: By planting endangered species, collectively we can help Mother Nature potentially find a naturally resistant variety of Butternut. The nuts are quite similar to other walnuts but with a milder flavour. They can survive in zone 2, but they must be planted somewhere zone 3 or warmer to produce nuts. The sap can be boiled to make walnut syrup, which tastes very similar to maple syrup but with notes of caramel and butterscotch.

Be mindful of the juglones in the in the roots/nut husks, they are toxic to many other species. They require a buffer of about 50'/30m from the edge of the trees canopy for juglone-sensitive plants. This article from The Garden Hoe has a helpful list of plants that tolerate juglones. However there are recent (2019) studies showing healthy soil high in organic matter and mycorrhizal fungi actually reduce the toxicity of juglones suggesting many plants can grow below juglans species in a healthy ecosystem - it will be interesting to see more study done in this area!

Species: Quercus prinoides or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: Dwarf Chinquapin Oak (also spelled Chinkapin) is native to southern Ontario and much of the eastern and central United States. It was first described in 1801 by German botanist Karl Ludwig Willdenow but was likely well-known amongst indigenous groups in its range for its edible acorns.

Why We Grow It: Dwarf Chinquapin Oaks are most well known for producing mild sweet acorns that can be eaten raw or processed, making them popular with humans and wildlife alike. They are also quite quick to start producing acorns, only taking 3-5 years where some larger species may take decades.

Species: Cornus florida

History: Native to parts of southern Canada, the eastern United States, and parts of Mexico, this shrub is now considered endangered in Ontario due to dogwood anthracnose fungus. Eastern Flowering dogwood has been used by indigenous peoples as a malaria remedy and to produce red dye, practices later adopted by European colonizers. The hard wood is good for products such as golf club heads and mallets among other things. This showy plant has quite the reputation in the US where it is the State tree and/or flower of three states. To add to this, in 1915 forty saplings were given by the US to Japan as part of the 1912-1915 flower exchange between Tokyo and Washington DC.

Why We Grow It: This small tree is a lovely addition to any property and the small red berries are attractive to various animals, although they are poisonous to humans. The fine-grained wood is also great for intricate carving and the tree has various medicinal uses.

Species: Cercis canadensis

History: Native to the eastern United States and parts of central Mexico, this tree may have once been native to southern Ontario but it is no longer found here naturally. It is still a fairly common sight since it has been widely planted as an ornamental tree due to its gorgeous profusion of pink flowers. The flowers and seeds have traditionally been eaten by indigenous peoples and people still enjoy them fresh or fried today, while some use the green twigs for seasoning.

Why We Grow It: This native tree grows well in any soil type, and puts on a show stopping bloom every spring producing millions of edible citrusy flowers. The pods it produces are edible too, and are best enjoyed when the young pods are sauteed or fried. The heart-shaped leaves add another level of appeal to the tree even when it is not flowering.

Species: Quercus robur or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: The English Oak is native to much of Europe where it is culturally significant in many countries. It appears on coats-of-arms, coins, and national emblems, and features prominently in folklore, stories, historical events, and even the legal process in Basque Country. There are numerous examples of exceptionally large and old English Oaks across Europe, such as The Majesty Oak in England with a circumference of 12.2m and the Stelmužė Oak in Lithuania which is believed to be over 1500 years old. The oaks are grown commercially for their durable wood and for ornamental purposes.

Why We Grow It: The English Oak's acorns are large (2.3-3cm long) and lower in tannins than red oaks, which make them more rewarding after going through the work of cracking and leaching the tannins to use them as a flour/food source. The wood is popular in barrel and cask making thanks to its elastic yet durable strength, and resistance to rot. Very long-lived trees, these majestic beauties can grow up to the ripe old age of 450 years old. It's also one of the few oak species that attracts and supports honey bees as a pollen source!

Species: Juglans regia or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: English Walnut (aka Persian/Carpathian Walnuts) is native from the Balkans to the Himalayas and China. It possibly originated in Iran and over time has been spread across the world by Alexander the Great, the Romans, trade along the Silk Road, and British colonizers. In Italy, there were legends of witches gathering under an old English Walnut tree in Benevento to perform sabbats which in turn has inspired works such as the ballet Il Noce de Benevento. Still commonly grown and cultivated today, China is the main producer of commercial walnuts.

Why We Grow It: Although they aren't native like our other walnut trees, English Walnuts are known for being easier to open than Black Walnuts and remain popular for a reason. Our seedlings come a mother tree near Listowel ON, an extra boon when Ontario grown English Walnuts are said to produce sweeter nuts than those from California! The sap can be boiled to make walnut syrup, which tastes very similar to maple syrup but with notes of caramel and butterscotch. The husks can be used to flavour beer, like hops.

Be mindful of the juglones in the in the roots/nut husks, they are toxic to many other species. They require a buffer of about 50'/30m from the edge of the trees canopy for juglone-sensitive plants. This article from The Garden Hoe has a helpful list of plants that tolerate juglones. However there are recent (2019) studies showing healthy soil high in organic matter and mycorrhizal fungi actually reduce the toxicity of juglones suggesting many plants can grow below juglans species in a healthy ecosystem - it will be interesting to see more study done in this area!

Native Tree Discount: Purchase multiples of this tree & enjoy the savings!

We try to grow as many Native North American Trees as we can; enjoy our bulk quantity discount (see below) and add to cart to see how much you save!

Species: Celtis occidentalis

History: Hackberries can be found in parts of southern Canada and in the eastern and central United States. The berries produced by the tree are commonly eaten by winter birds and mammals like squirrels. Indigenous peoples traditionally eat the berries raw or use them in several dishes. Although they tolerate urban conditions well, they are relatively uncommon as street trees except in Sombor, Serbia, and Bratislava, Slovakia where they have been planted extensively.

Why We Grow It: These beautiful native trees resemble the American elm, but without the disease issues. Both birds and butterflies enjoy this tree. The sweet small fruit taste like dates with a large crunchy pit that can be eaten or discarded. Thanks to their unusually high levels of proteins, calories, and vitamins, they are a great food source. You can learn more about Hackberries as a food source via this blog post by Alan Bergo.

Species: Prunus dulcis x P. persica

History: Little is known about the origins of Hall's Hardy almonds aside that they are actually a hybrid between an almond and peach. This hybridization allows them to better withstand colder temperatures that normal almonds cannot.

Why We Grow It: Hall's Hardy is a cross between an almond and a peach, giving it the cold hardiness to grow and produce small almonds in our climate. Although the nuts take quite a bit of effort to extract from their shells compared to regular almonds, they have a nice bitter-sweet flavour. They have higher levels of amygdalin than regular sweet almonds, so it is recommended to boil or roast them to remove the toxicity just to be safe, especially if consuming larger quantities. The trees are also quite attractive with ornamental pink blossoms in the spring.

Bareroot Peach & Almond Trees

We are very pleased to be able to offer almond trees to our customers. They are both challenging and rewarding plants to grow. However, due to the unique challenges of growing these trees, and the increased care required for their success, we regrettably cannot offer our standard 90 day guarantee. Please inspect your almond trees to your satisfaction when you pick them up at the nursery, or immediately upon arrival if they are shipped. For shipped trees, make your claim within 7 days of receipt of the trees. After 7 days of receipt, you will have been deemed to have accepted the trees in as-is condition.

Species: Juglans ailantifolia var. cordiformis or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: Heartnuts are a sport of the Japanese Walnut that have a heart-shaped shell and kernel instead of the usual elliptical shell. They have good commercial potential in the Great Lakes area where the climate is similar to that of Japan.

Why We Grow It: These trees produce an abundance of tasty nuts that are sweet than other walnuts and lack the bitter aftertaste. Ideally, they will produce heart-shaped nuts but since they are seedlings they may produce the usual rounder nuts of the regular Japanese walnut. They are sensitive to spring frosts for nut production, so they are best planted in a sheltered location.

Species: Gymnocladus dioicus

History: Kentucky Coffeetrees are native to the southernmost parts of Ontario and the midwestern United States. Despite its fairly large range, it is relatively rare today likely due to evolutionary anachronism. It is believed Kentucky Coffeetrees co-evolved with megafauna that are now extinct, so previously beneficial traits like the thick leathery pod around its seeds now hinder seed dispersal. Indigenous peoples have used the tree as a source of food by roasting the seeds and making a coffee-like drink, and the seeds have also been used as pieces in games and to make jewellery. Nowadays, the tree is planted ornamentally in urban areas.

Why We Grow It: This nitrogen-fixing, Carolinian tree produces seeds that may be roasted and used as a coffee substitute, but be aware the raw seeds are toxic! This tree boasts the largest leaves of any native tree, and it's considered a threatened species.

Native Tree Discount: Purchase multiples of this tree & enjoy the savings!

We try to grow as many Native North American Trees as we can; enjoy our bulk quantity discount (see below) and add to cart to see how much you save!

Species: Corylus heterophylla, C. americana, or C. heterophylla x C. americana

History: These hazelnut seedlings are grown from seed sourced from an open-pollinated, mixed hazelnut orchard at Grimo Nut Nursery. Since the orchard is open-pollinated, the resulting seedlings may be Asian hazelnuts, American hazelnuts, or hybrids of the two!

Why We Grow It: With such random cross-pollination, each seedling has the chance to be quite unique! Regardless of what you get, they will produce nuts that are excellent for a variety of uses!

Species: Catalpa speciosa

History: Northern Catalpa is native to the midwestern US where it was cultivated starting in the 1750s due to its resistance to rotting. This made it useful as fence posts and, rather unsuccessfully, as railroad ties. This tree has since expanded far beyond its original range as a commonly planted ornamental tree.

Why We Grow It: Catalpas make lovely ornamental trees, featuring large, heart-shaped leaves and twisting trunks. To further the visual appeal, they bloom annually with large, white flowers which turn into dangling bean pods.

Species: Aesculus glabra

History: Ohio Buckeye is native to Walpole Island in Ontario and some central and southern states in the United States. The Shawnee name for the tree is 'hetuck' which means 'eye of the buck' due to the nut's resemblance to a deer's eye. Indigenous peoples such as the Lenape traditionally use the nuts for medicinal uses, tanning leather, and jewellery. Ohio Buckeye is the state tree of Ohio and people from Ohio and graduates of Ohio State University are sometimes called 'buckeyes'. Unsurprisingly, the nuts have an important cultural place in Ohio. There is a candy resembling the nuts called 'buckeyes' that are popular and the nuts make numerous appearances in Calvin and Hobbes whose author is from Ohio. Its wood is too soft to be used for much and it has limited uses as a street tree since it is considered messy due to the nuts it drops.

Why We Grow It: Ohio Buckeye is an attractive ornamental tree with its large, palmate leaves and notable yellow flowers in spring. Although the tree is toxic and generally not fed on by wildlife, the large flowers are very attractive to a variety of pollinators including hummingbirds!

Tree Discount: Purchase multiples of this tree & enjoy the savings!

Enjoy our bulk quantity discount (see below) and add to cart to see how much you save!

Species: Maclura pomifera

History: Osage Orange is originally native to a small portion of Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. It was first introduced to European colonizers in the early 1800s by the Osage Nation, hence the name of the tree, who prized it for its use in making bows. It was then widely planted across the US in hedgerows thanks to the dense, thorny hedges it forms when pruned that were impenetrable to livestock. It was in fact one of the primary trees included in President Franklin Roosevelt's Great Plains Shelterbelt project which started in 1934 and by 1942 had resulted in 220 million trees being planted. The hard, rot-resistant, yellow wood was also useful for making fence posts, tool handles, and dye.

Why We Grow It: Although the fruit produced by the Osage Orange is not considered edible, this tree has plenty of other uses! It is still commonly planted as an ornamental tree and the bright yellow inner wood adds an extra level of appeal.

Species: Hamamelis vernalis

History: Ozark Witch-Hazel is native to the Ozark Plateau in the United States for which it is named. It has been cultivated ornamentally for its strong scent and unique flowering time, blooming from mid/late winter into spring. The name comes form a misspelling of the English word 'wyche' which means 'pliable' and 'hazel' due to the shrub resembling hazelnut shrubs. Interestingly, 'water witches' in the area did use Ozark Witch-Hazel branches in their water-finding rituals to divine the best locations to dig wells.

Why We Grow It: Witch-hazels are a unique plant for any property, sprouting stringy yellow flowers in the winter when nothing else is flowering. They produce woody capsules that forcibly pop open, launching the hard, black seeds up to 10m away.

Species: Salix sp, most likely Salix discolor

History: Pussy willows are native to North America, Europe, and Asia and are culturally significant in all three continents. They are a New Years decoration in China and Iran and have been used in various sects of Christianity for purposes such as replacing palm fronds as a decoration for Palm Sunday in Europe and America where palms do not grow.

Why We Grow It: A fluffy signifier of spring, these cute willows are also a great early pollen source for bees and have medicinal uses.

Photo by Huckleberry Hives.

Species: Carya ovata or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: Shagbark Hickory is native to parts of southern Ontario and much of the eastern United States. Much more common than the Shellbark Hickory, Shagbark Hickory is an important source of food for many species. Indigenous peoples also used the nuts as a food source and made the kernel milk into various dishes, along with using the wood to make bows. The strong wood is also used to make items such as tool handles and drumsticks that require extra durability. Check out this blog post by one of our customers to learn more cool history about these trees.

Why We Grow It: Shagbark Hickory produces an abundant crop of small hickory nuts every year and the sap can also be boiled for a unique flavored syrup (we haven't tried this yet, but would love to hear about it if you have!). The tree gets its name from the unique peeling bark, adding extra visual appeal wherever the tree is planted.

Species: Carya laciniosa or hybrid of C. laciniosa and C. ovata

History: Shellbark Hickory can be found naturally growing in scattered pockets of southern Ontario and parts of the northern and central United States. It is relatively uncommon in its native range due to its poor seed dispersal and human activity has made the tree even more rare. A wide variety of wildlife feeds on the nuts, the largest among the hickories, and there are some plantations although it is not commonly grown commercially as the nuts are quite difficult to crack. The wood, which is hard and strong yet flexible, is used to make furniture and tool handles while the inner bark has been used by indigenous peoples to make items such as baskets and snowshoes. Check out this blog post by one of our customers to learn more cool history about these trees.

Why We Grow It: Although difficult to crack, it is worth the effort to access the sweet nuts which are great eaten raw or baked into pies like pecans. The tree itself is quite attractive with unique bark that looks like it is flaking or peeling in strips once the tree matures.

Species: Alnus incana (likely subsp. rugosa)

History: Native to large portions of the Northern Hemisphere including parts of North America, Europe, and Asia, this widespread tree is often divided into six subspecies. We likely offer Alnus incana subsp. rugosa but with seedlings it is hard to say for sure. Indigenous people have used these trees for medicine and dyes, and they can also be used for erosion control. This subspecies in general is unique for its cold hardiness and ability to fix nitrogen, making it a useful companion plant in permaculture settings.

Why We Grow It: Named for the white lenticels that dot the reddish-gray bark, Speckled Alders can make a useful addition to a permaculture with their ability to fix nitrogen. However, keep an eye on this tree as it tends to spread via suckering (sending up new shoots) and layering (branches rooting into the ground) and can form dense thickets.

Species: Lindera benzoin

History: Spicebush is native to eastern North America, although in Canada it can only be found in Ontario. It has been used medicinally by several indigenous peoples and early land surveyors used it to find good agricultural land due to its propensity to grow in good soil. It remains a popular ornamental plant along with its uses for spices and teas. Spicebush is also the only host plant for the spicebush swallowtail.

Why We Grow It: If you want to source your own spices locally, try this aromatic, native shrub! The leaves and berries can be used as substitutes for cinnamon, nutmeg, and allspice. It is attractive to butterflies and the early bloom time means it is a good source of pollen in the spring. The shrub is also quite pretty in autumn when its leaves turn a bright yellow.

Species: Castanea dentata x mollissima

History: These seedlings are a cross between Chinese chestnuts and American chestnuts grown from seed from Grimo Nut Nursery. As a hybrid of Chinese and American chestnuts, these seedlings have blight resistance along with good cold hardiness.

Why We Grow It: This tree has incredible potential as a truly sustainable food source for humans. High in vitamins and starch, the nuts can be used to make a flour food staple, or pressed for oil to be made into bio fuel. For more inspiration and ideas in growing sweet chestnuts as a crop, we recommend the book Restoration Agriculture: Real-World Permaculture for Farmers by Mark Shepard.

Special Note: We take special care to grade out (remove) any of these seedlings that are showing visible thorns when we dig them in the fall. This increases the likelihood (although we cannot make any guarantees) that you will not have thorns develop on your Thornless Honey Locust Seedling. If you don't mind thorns on your Honey Locust, the ones we grade out are available here at a lower pricepoint.

Species: Gleditsia triacanthos

History: Thanks to its ability to tolerate a host of adverse conditions that would hinder or kill other trees, Honey Locusts have been cultivated for us as ornamental, urban trees. As a result, several thornless varieties have been developed including the mother tree for these seedlings.

Why We Grow It: Honey Locust has many benefits for permaculture and now growers do not need to worry about popping tires with thorns thanks to these thornless trees - though they are seedling so some may develop thorns though most will not; these can be top grafted with a thornless type if needed. Reaching 30 meters tall, this native nitrogen fixing tree benefits many including bees, wildlife, and even humans: we can use the sweet (honey flavoured) pulp inside their pods in baking, tea or for brewing beer. The durable, rot-resistant wood has a variety of uses.

Species: Liriodendron tulipfera

History: Tulip Trees are native to southern Ontario and the eastern United States. The wood of these trees has been used by indigenous peoples to make dugout canoes and to make furniture and cabinets. It is the state tree of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Indiana and George Washington planted some at his home at Mount Vernon in 1758 which are still standing today.

Why We Grow It: These fast growing trees are all around rather wonderful. Their oddly shaped leaves resemble a cartoonish cat head and in the spring and summer the trees bloom with greenish-yellow and orange tulip-like flowers. The flowers and later the seeds they produce are excellent sources of food for various animals.

Species: Carya illinoinensis or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: Pecan enthusiasts John Gordon and Gary Fernald, determined to get pecans to ripen regularly in Ontario, collected nuts and and grafting material from the earliest ripening pecan trees along the northern edge of their range in Iowa and Missouri. These were grown and tested at Grimo Nut Nursery and the best were chosen to form the Ultra Northern pecan strain.

Why We Grow It: Considering the amount of hard work that went into bringing these trees to Ontario, it's hard to turn down the ability to have a pecan tree in your own backyard. Like a regular pecan, the nuts can be used in a variety of ways for cooking and baking, such as the persimmon and pecan cookies Steph made (see pictures)!

Species: Carya ovata or hybrid. Our seeds are collected from trees that may have been cross-pollinated by closely related species so the resulting seedlings may be hybrids.

History: These are seedlings of Weschke Shagbark Hickories, a variety that was discovered in Iowa by Carl Weschke and named in 1926. It was selected for its excellent flavour.

Why We Grow It: While these seedlings will vary from their parents, the goal is that the excellent qualities of Weschke Shagbark Hickories will be passed along to its offspring! Weshcke Shagbark Hickories are known for having excellent flavour and thin shells that are easier for cracking. For more fascinating nut lore, enjoy this ebook.